In the following article, A. Clark examines the problem of bureaucracy from the point of view of a society going through a process of socialist transformation. He suggests that the continually advancing technological revolution in the field of computerisation and the communication and information revolution will serve as the material base to resolve most or even all of the problems associated with bureaucracy.

THE SOCIALIST REVOLUTION ENCOUNTERS BUREAUCRACY

The first successful socialist seizure of power by the working class did not end, but rather more aptly started with the problems of bureaucracy. Lenin’s initial optimism on having curtailed bureaucracy and its nefarious influence was short-lived. This was replaced by a more realistic view of the nature of the problem. In 1922, Lenin noted that

‘If we take Moscow with its 4,700 communists in responsible positions, we must ask: who is directing whom? I doubt very much whether it can be said that the communists are directing that heap. To tell the truth, they are not directing, they are being directed’. (Lenin: Vol. 33, pp.288-289)Here Lenin identifies what was to become a perennial theme of the Russian socialist revolution – the relation between the communists and the soviet bureaucracy, which included the struggle between them. Pre-Revolutionary Russia had behind it a long bureaucratic tradition and this bureaucratic past was superimposed, so to speak, on the new revolution. But in addition to the superimposition of this bureaucratic past on the new revolution, there was the fact that the state increasingly began to direct all aspects of the national economy. Even the collective farms, which emerged after the collectivisation drive in the 1930s, although not state institutions, were not completely autonomous from the state. The extension of state ownership and therefore the role of the state in the economy were bound to increase the size of the state administration and therefore a tendency towards bureaucracy was reinforced.

The increase in the size of the means of administration as a consequence of the extension of the regulatory influence of the state over the economy is not necessarily identical with what is referred to as the problem of bureaucracy, although it is often related to it. In other words, bureaucracy and administration are not the same thing even if usually closely related.

The view that state ownership necessarily leads to an increase in bureaucracy is not a valid argument, although it is a favourite argument for those who want to argue a case against socialism. Most theorists on bureaucracy disagree about the exact meaning of the term, and indeed, the problem of bureaucracy will arise mostly in cases where a bureaucracy is incompetent and dysfunctional. The soviet bureaucracy was a case in point. It had largely been inherited from Tsarism. Lenin had considered that, if the soviet bureaucracy rose to the level of competence of a bureaucracy that existed in one of the advanced bourgeois democratic republics, this would have constituted a big step forward for the Workers State. Had Russia gone through a long period of a bourgeois democratic republic, the problems of bureaucracy as it applies to the functional side of the question may hardly have arisen at all, at least no more than in an advanced capitalist country.

In historical terms Russia skipped a long period of bourgeois democratic development, and so the problems of bureaucracy were posed in a rather sharp, and at times, aggressive manner. To the functional side of the question of bureaucracy were added the socio-political problem of the state bureaucracy, or its leading stratum, consolidating itself into a special, privileged caste elevated above the masses.

BUREAUCRACY AND COUNTERREVOLUTION

The struggle against the soviet bureaucracy consolidating itself into a special privileged caste, which could usurp political power, or subvert the struggle for socialism, is part of the history of the Russian socialist revolution. Lenin in his writings on soviet bureaucracy refers to bureaucratic ‘grandees’. Svetlana, Stalin’s daughter, mentions Stalin’s reference to a ‘damned caste’. [1]

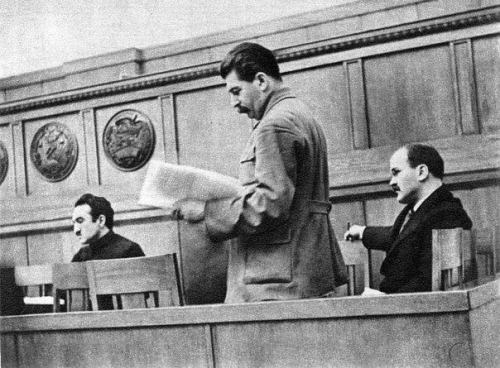

Stalin’s role here was decisive. He was in the forefront of the anti-bureaucratic struggle, which included the struggle against the soviet bureaucracy turning itself into a caste, which could potentially seize political power. This has been described by one writer as Stalin’s anti-bureaucrat scenario. [2] Thus in the middle and late 1930s the struggle against the enemies hiding in the soviet bureaucracy came to a head. Even as early as 1919, Lenin had pointed out that

‘The Tsarist bureaucrats began to join the Soviet institutions and practice their bureaucratic methods, they began to assume the colouring of communists and, to succeed better in their careers, to procure membership cards of the Russian Communist Party’. (Lenin: March 1919, Vol. 29; p.183)The nature of these purges has confused many bourgeois writers on the revolution. Pseudo-left elements, especially Trotskyists, misconstrue the purges completely suggesting that they represented counterrevolution. In reality, the purges were directed against the counterrevolution, which is the emerging new consensus of the more serious writers although they are anti-Stalinist.

That Trotsky could convince his small band of devotees that the purges were counterrevolutionary is not altogether surprising. After losing political power, Trotsky eventually abandoned the Leninist view on combating bureaucracy. Lenin had argued that the struggle against bureaucracy was a long-term process.

Trotsky rejected this view when he found himself outside of the communist party. On the question of fighting bureaucracy, Trotsky went over to a short-term perspective, misleading those who were ignorant or foolish enough to follow him, to believe that the problems arising from bureaucracy could be resolved by means of a ‘political revolution’. This is precisely what Lenin had warned against, i.e., making a political platform out of the issue of bureaucracy.

Trotsky, rejecting Lenin on this issue and his slogan of ‘political revolution’ against the soviet bureaucracy could only serve the interest of bourgeois democratic counterrevolution. It is perhaps necessary to add here that when the Stalinist leadership turned against soviet bureaucracy, they were not going against Lenin’s advice on how to combat bureaucracy. [3] The Stalinist drive against the soviet bureaucracy served several different purposes. For Stalin, like Lenin, there could be no talk of smashing or overthrowing the soviet bureaucracy. While Trotsky and his supporters were putting forward the ultra-left theory about a counterrevolutionary ‘Stalinist’ bureaucracy, the Stalinists, guided by Marxism-Leninism saw the issue not in terms of overthrowing the supposedly counterrevolutionary soviet bureaucracy but rather purging the counterrevolutionary elements in the soviet bureaucracy.

It is clear that Marxist-Leninists, like Stalin, rejected Trotsky’s short-term strategy for fighting bureaucracy based on the idea of a political revolution. Trotsky had reached this conclusion not because it was scientifically correct, but rather because he saw it as the only means of regaining political power. On the question of fighting bureaucracy, Stalin adhered to Lenin’s line.

The more serious bourgeois researchers into these matters come closer to the truth than any Trotskyist interpretation, thus Getty, when referring to the purges of the middle and late 1930s concludes that

‘The evidence suggests that the Ezhovschchina – which is what most people mean by the ‘Great Purges’ – should be redefined. It was not the result of a petrified bureaucracy stamping out and annihilating old radical revolutionaries. In fact, it may have been just the opposite. It is not inconsistent with the evidence to argue that the Ezhovschchina was rather a radical, even hysterical, reaction to bureaucracy’. (J. Arch Getty: The Origins of the Great Purges: The Soviet Communist Party reconsidered – 1933-1938; p.206) [4]In Getty’s view, then, the Stalinist purges constitute a radical, ‘even hysterical, reaction to bureaucracy’. This was certainly the apogee of radical Stalinist anti-bureaucratism. For Stalin the soviet bureaucracy had to be purged of all actual and potential counterrevolutionary elements. It was not a question of overthrowing the soviet bureaucracy, as the ultra-left Trotskyists would have, but rather of purging it of all counterrevolutionary elements. Many believe that the Soviet Union would not have stood up to the later Nazi aggression had this action not been taken.

Stalin’s anti-bureaucratic credentials can therefore be clearly established, although the problems of bureaucracy remained and could not be solved until society had reached a higher technical level.

In one form or another, to one degree or another previous socialist regimes have had to face this problem. The Titoite revisionists of Yugoslavia saw the solution in terms of decentralisation. In socialist Albania, the Cultural Revolution, with bureaucracy as one of its targets, began when in 1966 the Central Committee sent an open letter to all party members attacking the evils of bureaucracy. There began a significant reduction in the size of bureaucracy and Albania copied the Maoist line. Those bureaucrats who remained had to spend one month each year performing service in manual labour to keep them in touch with the working class and peasantry.

In truth though, this approach, whether in China or Albania, had no long-term benefits. It did however succeed in alienating the administrative staff, who naturally saw themselves as victims and were resentful of the disruption caused to the economy by these anti-bureaucratic drives.

As previously pointed out, the struggle against bureaucracy in a socialist country has two sides to it. First, there is the struggle against the dysfunctional aspect of bureaucracy. This includes the gradual reduction of the size of bureaucracy, while improving its administrative performance. The other aspect of this struggle is that aimed at preventing the bureaucracy, in particular its managerial layers separating itself from the rest of society – and becoming a privileged caste which can seize political power. Because bureaucracy has no particular ideology or ownership of property holding it together the possibility of it actually seizing political power is rather more problematic than is often realised.

THE WITHERING AWAY OF THE STATE AND BUREAUCRACY

For Marxists, the state is the inevitable product of class society. As classes fade away, the state in the sense of bodies of armed men and all its appurtenances, for the repression of one class by another will fade away. Bureaucracy is one of the forms in which state power in class society expresses itself. The function of the state is to defend a particular social set-up and its ruling class. This applies to socialist society with the same force as it applies to capitalist society. As long as capitalism and the bourgeoisie exist all talk about the withering away of the state is foolhardy in the extreme.

The Soviet State illustrates this point clearly. It had to grow in power and strength in order to resist the pressure of imperialism and world reaction. Those, like the Yugoslav revisionists who attacked Stalin for not promoting a premature withering away of the state, simply demonstrate their anarchist and anti-Marxist conceptions of this process. The state rises and falls with class society. Its departure from the historical stage cannot precede the departure of classes.

Just as Marxist-Leninists want a state that serves socialism, they want the bureaucracy to serve socialism as well. Stalin’s struggle with the soviet bureaucracy is well known and documented. This struggle was certainly inevitable. The essence of this struggle was to get the bureaucracy to serve the interest of socialism. But Stalin understood the contradictory nature of the struggle against bureaucracy. He knew the communist must struggle against bureaucracy while using it at the same time. Bureaucracy is a means of administration by specialists, which is deployed in the interest of socialism by the political leadership of the working class, while at the same time fighting its negative aspects.

When the state takes over the running of industry this can lead to an increase in its administrative functions, and hence bureaucracy. However, it is wrong to view an increase in administrative bureaucracy as a logical result of socialism per se. It is rather a result of the technological level of the given society. Thus, the state of technology comes into play when we consider the extent of the process of bureaucratisation. In other words, the process of bureaucratisation is determined by science and technology.

In today’s world of the continuing rapid advances in the technological revolution, with no end in sight, administrative systems are bound to reflect technological advances. This would suggest that administrative systems will decrease in size while increasing in their ability to process and control information. The old views that state ownership and socialism lead inevitably to an increase in administrative bureaucracy will no longer be plausible. Implicit in all this is the withering away of the state and bureaucracy.

This process, i.e., the withering away of the state and bureaucracy is part of the process of achieving communist society based on advancing technological revolution. For these reasons, it is incumbent on serious Marxists to reject pseudo-left Trotskyist theories that bureaucracies under socialism can be overthrown by means of ‘political revolutions’.

A. Clark.

Notes

[1] Svetlana Alliluyeva: 20 Letters to a Friend; p. 174.

[2] See Lars Lih’s introduction to: Stalin’s Letters to Molotov.

[3] The term ‘Stalinist’ refers to those who supported Stalin.

[4] The word ‘Ezhovschchina’, from the name Ezhov, sometimes spelt Yezhov, was the name of Nikolai Ezhov, who replaced Yagoda as head of Soviet security and subsequently put in charge of the purges.

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen